Background

You never know what situation you will find yourself when you are working for the Department of Defense. I was 24 years old and a 2nd Lieutenant in the US Air Force. My first operational assignment was as a Navigator assigned to an Air Refueling Squadron (KC-135s), based at Grissom Air Force Base in Bunker Hill, IN. When I reported there in early 1973, I only flew a month or six weeks of Strategic Air Command (SAC) missions (all training, i.e. air refueling, missions) there and participated in SAC Alerts, which was the primary function of SAC.

SAC Alert was a real mission in which aircrew and their airplanes were on 24 hour “alert” status. This means that the airplane is fully fueled, maintained and ready to launch within minutes. The crews (on a one-week rotation) stay in a housing facility (colloquially called the “mole-hole” because it was partially constructed underground) which is located adjacent to the airplane parking apron (colloquially called the “Christmas tree” because of the manner in which the airplanes were parked in a staggered formation that from above had that shape).

The Vietnam War was in the Peace Treaty Negotiation Stage at the time of my assignment. The Treaty itself was signed on January 27, 1973. The last military unit withdrew from South Vietnam on March 29. US military operations did not end then however, as intelligence and reconnaisance flights and operations continued based primarily from Kadena AB in Japan and bases in Thailand. These were extensions of Operation Bullet Shot which had been the last major bombing of North Vietnam in December 1972, which had triggered the Peace Accords. Within a month after I reported to Grissom, I was on my way with my first aircrew to Kadena Air Base in Japan for a 90-day TDY (temporary duty assignment). We didn’t have a lot of flying to do, but (before March 29) we refueled an RC-135 (Recon Aircraft) over the Gulf of Tonkin and near Hainan Island, China. This sortie was my one and only combat mission in Southeast Asia as after March 29 there was no longer “combat” for the United States, even though recon flights continued from Kadena and Thailand until 1975 (and probably later) after the fall of Saigon, South Vietnam.

We returned to Grissom by the end of May (90 days) to the SAC training missions and alerts. But shortly thereafter this crew was split. I was placed with a different crew probably in June 1973. This is when my espionage saga begins.

Drafted Into “Burning Light”

By early July my new crew was tasked with another 90 TDY, this time to U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Air Base. We were to proceed to Hickam Air Base in Honolulu and thence to Thailand as part of an extension of the Young Tiger Mission (supplying air refueling) for the Strategic Wing based at U-Tapao. Even though the Vietnam War was over for the US, the recon mission over Laos and Cambodia (and South Vietnam- shh! it’s our little secret) was still active. Moreover, over the 1973 - 1974 time-frame we were going to support Operation Lima Mike, a tanker task force responsible for ferrying back combat fighters from their temporary bases in Thailand (e.g. Ubon, Udorn, Tahkli) back to the US (since their usefulness in Southeast Asia was now moot for the most part).

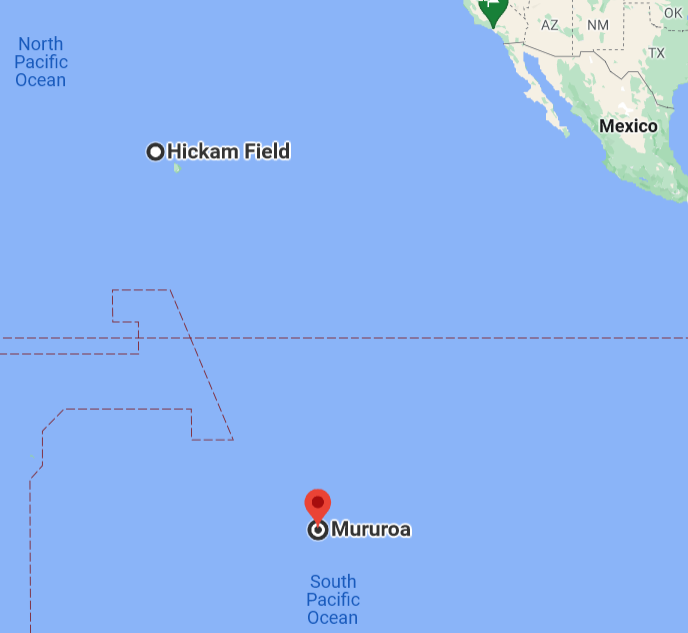

We arrived at Hickam in early July. When we got there our airplane and crew was drafted (for lack of a better term) for a new, temporary mission – Burning Light. Burning Light was part of a nuclear collection effort (of the Defense Nuclear Agency nicknamed Hula Hoop (in 1973). The overall exercise also included Navy surface ships, drones and helicopters located near French Polynesia. The mission had one objective, to support the development of miniaturized, inexpensive, highly sophisticated system for analyzing nuclear explosions and to gather information that would improve the US’ ability to predict the effects of low-altitude nuclear weapons. France conducted its nuclear testing about 3,000 mile south southeast of Hawaii at Mururoa Atoll in French Polynesia. The tests took place in June through August window due to favorable winds and other climatic factors. 1973 and 1974 was a time of extensive nuclear testing by the French.

|

| Relative locations of Hickam AB and Mururoa Atoll (3000 miles apart) and showing the SW coast of the USA for reference |

The Mission

In 1973 the Air Force Special Weapons System Center of the Aircraft Systems Command provided two NC-135As to gather the nuclear data from the tests. One plane was under the sponsorship of the Defense Nuclear Agency (DNA) and the other, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). The other part of the mission deployment were nine KC-135 tankers. There were four reconnaissance air crews, thirteen tanker crews and supporting aircraft maintenance personnel. These were all deployed to Hickam between July 12 and 19, 1973. Our crew was apparently “borrowed” for a mission early in the program as we were not specifically scheduled for this operation (as far as I know), i.e. a +60 day TDY at Hickam. There were apparently some difficulties with one or more of the KC-135 airplanes or crews and we (finding ourselves at Hickam for a few days rest before going to Thailand) were a convenient substitute. Our mission was apparently the first mission on July 21.

|

| An NC-135A |

There were five nuclear tests conducted that summer – two in July and three in August. Both NC-135s and eight tankers were launched for each mission. And while SAC still provided the NC-135A air crews, the DNA and the AEC paid for the planes’ upkeep. However, the Air Force still refueled the planes to and from their destinations. Also serving aboard the NC-135As were personnel assigned to the DNA, the AEC, the USAF Security Service, and the Air Force Technical Applications Center, the “guys in back”.

On top of all that, all the 135s (NC and KC) relied on water augmentation — or shooting water into the plane’s jet engines during takeoff to produce more thrust. This noisy (and smoky) practice allowed the planes to take off with a full tank of fuel. But it was too noisy for Honolulu International Airport (Hickam) which had prohibited water-augmented takeoffs between nine o’clock at night and seven o’clock in the morning — every day, as its standard operating procedure. Pressure from Hawaiian politicians and environmental groups prevented the Air Force from getting an exemption from these rules. Because the usual time for the atomic tests were about 0700 or 0800 local time, give or take, this required a 0000 takeoff time (mid-night) at Hickam.

Departures from usual operational procedures and French technical difficulties had turned the Defense Nuclear Agency’s decision to launch the NC-135As largely into “guess work.” For one, the missions had to follow a strict schedule so the planes would arrive over Polynesia, almost 3,000 miles away, at the right times. The French often delayed or completely canceled tests due to bad weather and technical problems. The Air Force couldn’t guarantee that all of the necessary tankers would be ready on such short and irregular notice. The crews would be briefed on the apron in the aircraft during a kind of stand-by alert.

|

| U.S. National Archives satellite reconnaissance image of the Mururoa Atomic Test Site in French Polynesia, May 26, 1967 |

Our mission depended on the quality of the intelligence of collateral agency sources which could identify the time and date of these French tests. Last minute postponements or delays and cancellations could affect the amount and quality of the data collected or prevent it entirely. Because the NC-135A refueled lastly before entering orbit for 2.5 hours before beginning its return to Hickam, accurate, on the scene intelligence information from these sources was critical to the mission success.

|

| KC-135s on Flight-line at Hickam AFB, Honolulu |

Bibliography:

- Office of the Historian, Strategic Air Command. History of SAC Reconnaissance Operations, FY 1974, August 28, 1975. (Extract) Secret, Source: Freedom of Information Act Request. This extract provides information about BURNING LIGHT monitoring of French nuclear tests during the 1973/1974 fiscal year.

- History Division, Strategic Air Command, SAC Reconnaissance History, January 1968-June 1971, November 7, 1973. Notes the role National Security Agency intercepts played in providing advance notification of tests, allowing BURNING LIGHT missions to be in the required area at the time of the tests.

- How the U.S. Air Force Spied on French Nuke Blasts, Special tanker planes snooped on Pacific tests, by JOSEPH TREVITHICK, War is Boring, March 28, 2015

- U.S. Intelligence and the French Nuclear Weapons Program, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 184, Edited by Jeffrey Richelson

- Spying on the Bomb: American Nuclear Intelligence from Nazi Germany to Iran and North Korea, By Jeffrey T. Richelson

No comments:

Post a Comment