Prologue

Who?? and What??

I grew up in Tamaqua. Everyone who has grown up in Tamaqua knows about its “origin”. The story is that, how, in 1799, one Burkhardt Moser emigrated from Northampton County over the Blue Mountain and settled near the confluence of the Panther Creek and Little Schuylkill River (then known as the Tamaqua - or Tamaguay - Creek). Here he built a sawmill and later his permanent residence in 1801 (which today remains standing, in part, at the rear of 307 East Broad St). Moser was a lumberman and farmer and with a small cadre of family and friends, a small settlement took root. In 1817 coal was discovered here and a railroad was built in 1831 to transport it and as they say, the rest is history.

|

| Burkhardt Moser's original log cabin dwelling built 1801 in Tamaqua, PA |

The (William) Penn Proprietorship “purchased” the land upon which the town later arose in the mid eighteenth century. This acquisition was made under the Purchase of 1749 Treaty. What was to become Tamaqua was first assigned to Northampton County. The northern-most township in this part of Northampton County was Lynn Township and initially this land north of the Blue Mountain became part of Lynn Township. But in 1762, a township north of the Blue Mountain was created called Penns Township. Later in the first decade of the 1800s, Penns Township was further divided into East Penn (eventually becoming part of Carbon County decades later) and West Penn Townships. The area north of new West Penn Township was further sub-divided into Rush Township.

With the exception the fertile farmland immediately north of the Blue Mountain (near Lizard Creek) very little migration to the new land took place. The first reason for this was the effect of the French and Indian War in the 1750s. Subsequently at its conclusion in 1763 and a little more than a decade later the American War for Independence began and lasted until 1783. This was the second reason for the slow migration.

But the lack of migration here did not mean that the land was ignored. People purchased the new land and began to establish individual ownership. There was a 5-part process to create deeds (and have individual owners buy the lands). The original and normal process for obtaining land in Pennsylvania was set up under the authority of Crown of England for the colony of Pennsylvania:

1) the applicant submitted an application for a land tract;

2) the Pennsylvania Land Office (after the payment of a fee) issued a warrant, or order, for a survey;

3) the next step was to pay another fee for the survey and wait until a deputy surveyor could be assigned to do the work;

4) the survey with a precise description and map of the tract was returned to the Land Office for issuing the final title or “patent”; and

5) the patent (upon payment of yet another fee) was issued and a name given to the tract by the patentee. (From the years of the Penn Proprietorship until about 1810, tracts were given names to make it easier to track them when they changed ownership. Moser named his tract, "Amsterdam.")

It is estimated that approximately 70% of land within Pennsylvania was transferred from the colonial or, later, state government to private owners using this process. In the other 30% of land transfers, different processes were used. Many early settlers settled on vacant land before paying for and receiving government authorization (a warrant), often because they were beyond government offices or because Pennsylvania had not acquired the territory yet through treaties with Indians. Rather than receiving a “warrant to survey” ordering a surveyor to come and survey the land as in the normal process, they received an “order to accept” a survey conducted after their settlement. In this case, the survey states it was conducted on a “on a warrant to accept” and the word “accept” is noted in the relevant Warrant Register.

Sometimes, many years passed between the steps. Moreover, the process was rife with land speculation. Many warrantees were not interested in the land to have as their own, but would purchase the land in order to sell to those who did desire it as farmers, lumbermen or others as patentees. Furthermore they could be an additional step of land speculation in which both the warrantee and patentee would be speculators, intent on subdividing their tracts and reaping the expected profits.

The process, for example, for Burkhardt Moser's patent occurred as follows:

1) John Burkhardt Moser applied for a Warrant in Northampton County on June 27, 1768 (A-21-253).

2) However, the survey was not completed and returned until November 9, 1775. Moreover, Moser did not turn the warrant into a patent before he died in 1807.

3) Later his son Burkhardt received a deed (accept to warrant) on June 21, 1809 (H-1-138), 41 years later.

By this time Burkhardt (the son) had settled in Tamaqua and began a small but growing community there. The elder John Burkhardt Moser never moved from Lynn Township and died in 1807.

|

| Warrant of Burkhart Moser, dated June 21, 1809, Rush Township, Northampton County, Pennsylvania |

Other Developers of Tamaqua

Burkhardt the Elder was actually the second person to apply for ownership of land in what was to later become Tamaqua borough limits. Nine other individuals (or groups) were to purchase land (warrantees) which eventually became Tamaqua borough limits. It is important to recognize that these warrants and patents included substantial acreage (from 200 to 400 and sometimes more, acres for each patent) and only a portion of the original deeds constituted property in the borough limits. For example, Moser’s final deed was 221 acres, with about 50% being east of the future town limit (an area later known as Greenwood and Rahn Township).

The following is a summary of the Warrantee / Patentee records for what was to become the borough (limits) of Tamaqua:

# |

Warrantee |

Date of Warrant |

Patentee |

Date of Patent |

9 |

John Wood |

7/22/1784 |

John Reiner |

5/9/1786 |

10 |

Peter Aston |

7/10/1793 |

James Wilson |

9/17/1794 |

11 |

Aaron Bowen |

11/23/1785 |

Aaron Bowen |

2/4/1786 |

25 |

Frederick Boller |

11/18/1793 |

James Wilson |

9/16/1794 |

26 |

Jacob Hauser |

5/6/1776 |

Jacob Hauser |

7/15/1782 |

27 |

Peter Scholl |

6/2/1768 |

Charles Graff et al |

1/4/1828 |

28 |

J. Dunn et al |

8/13/1794 |

Aaron Winder et al |

5/30/1854 |

29 |

J. Burkhardt Moser |

6/27/1768 |

Burkhardt Moser |

6/21/1809 |

40 |

Melchior Christ |

8/10/1794 |

Thomas Armat |

1/5/1798 |

90* |

Joseph Clark |

11/18/1793 |

Andrew Douglass |

9/16/1794 |

* See the extreme NW corner of the Tamaqua boundary. Not IDed by number on map below. |

||||

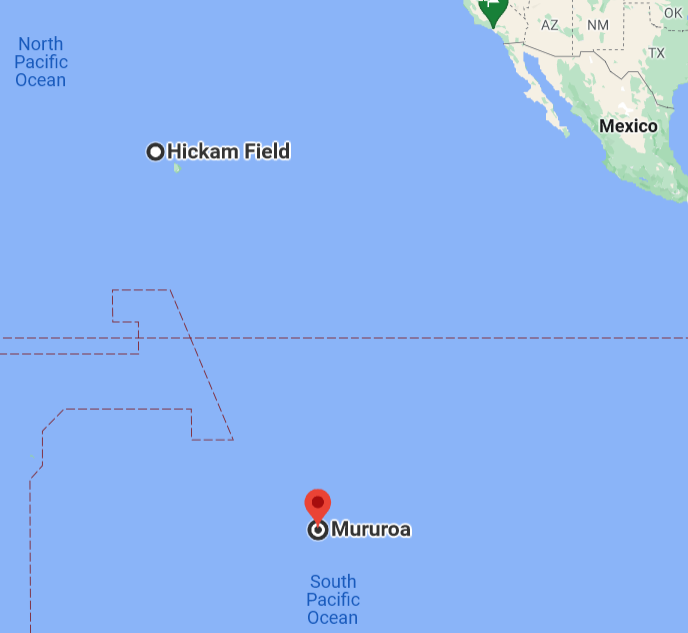

The map below shows the relative location of the tracts of land that would constitute the area of the future borough of Tamaqua:

|

| Map showing the Patents/Warrants issued on land later to become the Borough of Tamaqua (see parallelogram, outlined in black); Burkhardt Moser's plot shown outlined in green. See Warrantee Maps for Rahn Township. |

Land Speculation and James Wilson

The Founding Fathers

Land speculation was a common preoccupation among the Founding Fathers. For some it became an economic affliction. As noted by Albert J. Beveridge in his The Life of John Marshall, Volume II, p. 202,

“Hardly a prominent man of the period failed to secure large tracts of real estate, which could be had at absurdly low prices, and to hold the lands for the natural advance which increased population would bring”.

For many, such speculation would prove a hazardous preoccupation. Virginia’s Henry Lee and Pennsylvania’s Robert Morris and James Wilson ended up in jail because of their debts from land speculation. Washington biographer James Thomas Flexner in his George Washington: Anguish and Farewell (1793-1799), p. 371, noted that land speculation was,

“a fundamental aspect of American economic life, but it had become in the last few years an extremely tricky one. General [Henry] Knox was above the knees in financial trouble because of the new settlements he had started in Maine.”

Speculation in land became particularly rampant in the early 1790s when the stability of the new republic seemed assured. Describing the process of speculation, historian Forrest McDonald in his The Presidency of George Washington, p. 10, wrote:

“One worked or connived to obtain a stake, then worked or connived to obtain legal title to a tract of wilderness, then sold the wilderness by the acre to the hordes of immigrants, and thereby lived and died a wealthy man. Appropriately, the most successful practitioner of this craft was George Washington, who had acquired several hundred thousand acres and was reckoned by many as the wealthiest man in America.”

So in the 1790s, there were rich speculators and there were successful farmers and businessmen who bought up large tracts of land (400 acres) with the goal of subdividing the area and sell to migrant immigrants in smaller parcels (5-10 acres). Tamaqua was no different and one man who was well known, and who was also a founding father, was James Wilson. He owned two plots which are (in part) contained within the Tamaqua town (old) limits (see above). He owned what was to become upper Dutch Hill and part of the North Ward, as well as the southwestern part of the South Ward.

James Wilson

James Wilson was born in Leven, Fife, Scotland on September 14, 1742. He immigrated to Philadelphia in 1766 and became a teacher (Latin tutor who became an English professor) at the College of Philadelphia (later to become the University of Pennsylvania). After studying law under John Dickinson (a legendary Pennsylvania attorney and fellow Founding Father), he was admitted to the bar and set up a legal practice in Reading, Pennsylvania. He moved to Carlisle, where he operated a farm and became a founding trustee of Dickinson College.

He wrote a well-received pamphlet arguing that Parliament's taxation of the Thirteen Colonies was illegitimate due to the colonies' lack of representation in Parliament. He was elected twice to the Continental Congress, and was a signatory of the United States Declaration of Independence.

After some time, Wilson moved his family back to Philadelphia. Upon holding the University of Pennsylvania’s first law lectures – which may also have been the first in the United States – James Wilson became known as the founder of what is today the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School.

In 1787 he was a major force in drafting the United States Constitution. Wilson served on the Committee of Detail, which produced the first draft of the United States Constitution. He was the principal architect of the executive branch (see McConnell, Michael W. (2019). "James Wilson's Contributions to the Construction of Article II". In Barnett, Randy E. (ed.). The Life and Career of Justice James Wilson (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown Center for the Constitution. pp. 23–50 and p. 219) and an outspoken supporter of greater popular control of governance, a strong national government, and legislative representation proportional to population. Along with Roger Sherman and Charles Pinckney, he proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted slaves as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of representation in the United States House of Representatives. While preferring the direct election of the president through a national popular vote, he proposed the use of an electoral college, which formed the basis of the Electoral College ultimately adopted by the Convention. After the convention, he campaigned for the ratification of the Constitution, with his "speech in the statehouse yard" reprinted in newspapers throughout the country, and he opposed the Bill of Rights. Wilson also played a major role in drafting the 1790 Pennsylvania Constitution.

|

| Lawyer, Founding Father and Supreme Court Justice, James Wilson |

However, Wilson was, as noted above, one of the numerous Founding Fathers who was a land speculator. During 1779 he began actively taking up the development of the country, not only in Pennsylvania and other States of the East, but in the new territories of the West, over which the States were quarreling but which was bound to become National domain. He was an owner of the combined Illinois and Oubache (Wabash) Land Companies, and later became their attorney and president, and from this time until his death it is doubtful if there was a greater individual land owner in America. Two years later he owned 300 shares in the Indiana Land Company, whose bounds covered a good part of two eventual States, Indiana and Illinois. Within a dozen years or so he had sold a half million acres to the Holland Land Company and bought over 4,000,000 acres scattered in all parts of the South from the Potomac and Ohio to the western boundary at the Mississippi. His papers show that he was not merely a speculator, but, as he put it to certain Dutch capitalists, proposed to develop our need with their abundance of men and money. He outlined to them a plan of immigration and development imperial in its scope. (From James Wilson and the Constitution: the opening address in the official series of events known as the James Wilson Memorial by Burton Alva Konkle [Philadelphia], 1907)

As an example of this (and after he began his tenure on the Supreme Court in 1792), Robert Morris and John Nicholson incorporate the Pennsylvania Population Company with a capital of $500,000 to raise money on 500,000 acres in northwestern Pennsylvania; shares are sold at $200; John Nicholson takes 400 shares and another 100 for Robert Morris; other directors include James Wilson, Gen. William Irvine (1741-1804), Walter Stewart, Theophile Cazenove (representing Dutch investors) and Aaron Burr. The object is to sell land in small parcels to settlers. (See Arbuckle, Rappleye, Chernow.)

He continued speculating near his adopted home in Pennsylvania. He established mills and factories in Northampton County and speculated in the Pennsylvania interior including upcountry Northampton and Berks Counties, where Tamaqua was to be born. In 1794 Wilson owned over 6,000 acres in northern Penns Township (what was to become Rahn Township) including two parcels in Tamaqua. Wilson had been described as owning large areas of coal lands in Northampton County, which he later sold in 1796 to Benjamin R. Morgan of Philadelphia and General Henry Lee of Virginia. (See The History of the Supreme Court, Volume 1, Gustavus Myers, p.114, Chicago, Charles H. Kerr & Co. 1912.) It is not clear that the Tamaqua parcels were part of these “coal” lands, although both parcels were certainly future collieries – parcel 10, with the LCN Number 14 and parcel 25, near the West Lehigh Colliery.

However, Wilson suffered financial ruin from the Panic of 1796–1797 and was briefly imprisoned in a debtors' prison on two occasions (while on the Supreme Court). He suffered a stroke and died in August 1798 (in North Carolina), becoming the first U.S. Supreme Court justice to die. He was replaced on the Supreme Court by Bushrod Washington, George’s cousin (appointed by President John Adams). His son, Bird Wilson, was still settling his vast affairs in 1852, decades after Wilson’s death.