Behind the Front Lines

Military Camp Towns

On December 14, 1915 the 121st Reggimento Fanteria is relieved at the front and goes to the rear at the municipalities of Campolongo and Località Armellino (Ruda). From the spring of 1915 field hospitals for wounded soldiers, warehouses, camps for the handling of prisoners, lodgings, recreational and entertainment centers for soldiers and for civilian employees who were engaged in the construction of military facilities started to appear in towns and villages in the Veneto plains, in Belluno, in the Carnic and Julian Alps and in the Friuli plains. Unlike built-up areas on the front, towns and villages in zones behind the frontlines were not evacuated. In these cases, civilians lived alongside the presence of four million soldiers for a period of two and a half years, adapting their habits to the customs of military personnel.

|

| Houses near Località Armellino today |

On the other hand, for many Italian soldiers, military service and mobilization represented the first time they had visited other parts of their own country, and often the first time they had been on a train. While army life of course meant time at the front, troop rotation systems meant that in theory a mobilized unit spent only 25 percent of its time in the trenches (although the Brigata Macerata spent 32% of its time in 1915 in the front lines). The remaining time was spent in reserve areas or rest zones away from the front lines, which could include many of the towns and cities of the Veneto region. During these periods men engaged in labor, training exercises and (limited amounts of) rest and recuperation activities. New recruits spent a minimum of two or three months in training camps before deployment, while some units served within Italian territory on garrison duty, maintaining public order and defending ports against naval bombardment. Thus wartime experience meant not only life in the trenches but an unprecedented degree of travel around the country, and to judge from men’s (from the peasant and lower middle classes) letters, diaries and memoirs, it is clear that most were fascinated by visiting new parts of Italy and meeting new people from other areas.

One of the best descriptions of what life was like behind the front lines has been found of Campolongo, where my father initially joined his unit on December 2, 1915. Campolongo al Torre (the Torre is a river that is a tributary of Isonzo River) was occupied by Italian troops (shortly after war was declared – May 23) on the morning of May 24, 1915 and became a rear staging and command area. The town was actually part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (in Gradiška (Cervignano sub-district), Küstenland) since early in the nineteenth century (being passed on from the defunct Republic of Venice). After Austria-Hungary began World War I most of the young local men were soldiers of the Hapsburg Army. When Italy declared war against Austria in May 1915, the Austrian government left the low lying areas near the then Italian border and occupied and fortified the surrounding mountains and heights east of the town on the Karst Plateau, assuming a defensive posture. Campolongo would immediately be transformed into an important Italian army post and hundreds of thousands of young Italian soldiers were present for over two years until 1917 when the Italians fled during the Battle of Caporetto.

|

| Campolongo il Torre (Cjamplunc) Küstenland, Austria in 1915 before the War |

A local parish priest, Don Parmeggiani, one of the few priests left in their place by the Italians because of their irredentist sentiments, recalled that the average daily number of soldiers housed in the town and in the adjacent countryside was about 12,000. They were part of regiments at rest after tserving at the front line but also some were responsible for providing everyday services in the rear.

|

| Villa Marcotti - XIII Army Corps HQ |

In the Villa Antonini Chiozza (aka Marcotti), now the Town Hall, the Command of the XIII Army Corps (Corps d’Armata) which was led by Generals Cinneio and Grazioli and others, was situated. This was a headquarters of considerable importance that saw the coming and going of personalities such as Cadorna, Salandra and Louis Barthou, the French Foreign Minister, as well as Russian representatives.

In the hamlet of Cavenzano there is another Villa Antonini (now a ruin), at the time of war owned by the Trieste entrepreneur Rodolfo Brunner, who spent part of the war years there. While he was interned by the Italians for his Habsburg sympathies, his son Guido enlisted (sottotenente) as an “irredenta” volunteer dying on June 6, 1916 on Monte Fior (as part of the Strafexpedition defense) and being awarded a Gold Medal for Military Valor.

In the town there were also visits from the King Vittorio Emanuele III who sometimes ascended (the first time on 6 June 1915) on the bell tower for a view of the Front lines, together with Emanuele Filiberto Duke of Aosta (Commander of the Third Army) to observe the military operations of the nearby front. Later he preferred the more advanced bell tower located in Romans d'Isonzo.

Among the services there were the 60th-75th-101st-132nd field hospitals that were visited several times by the Duchess of Aosta, who served as Inspector of the Italian Red Cross. There was also an important laundry center, where the military could bathe and their clothes were washed and sterilized, so the journalist Attilio Frescura in his war diary called Campolongo "the cloak of the Army," and two brothels.

|

| Elena d’Orleans Duchess of Aosta General Inspector of the Volunteer Nurses possibly at a Campolongo Hospital |

A school for Officer Candidates was also established in town and housed in some stables.

Campolongo also hosted soldier Giuseppe Ungaretti who wrote a collection of poems called "L'ALLEGRIA" dated as – Campolongo, 5 July 1917.

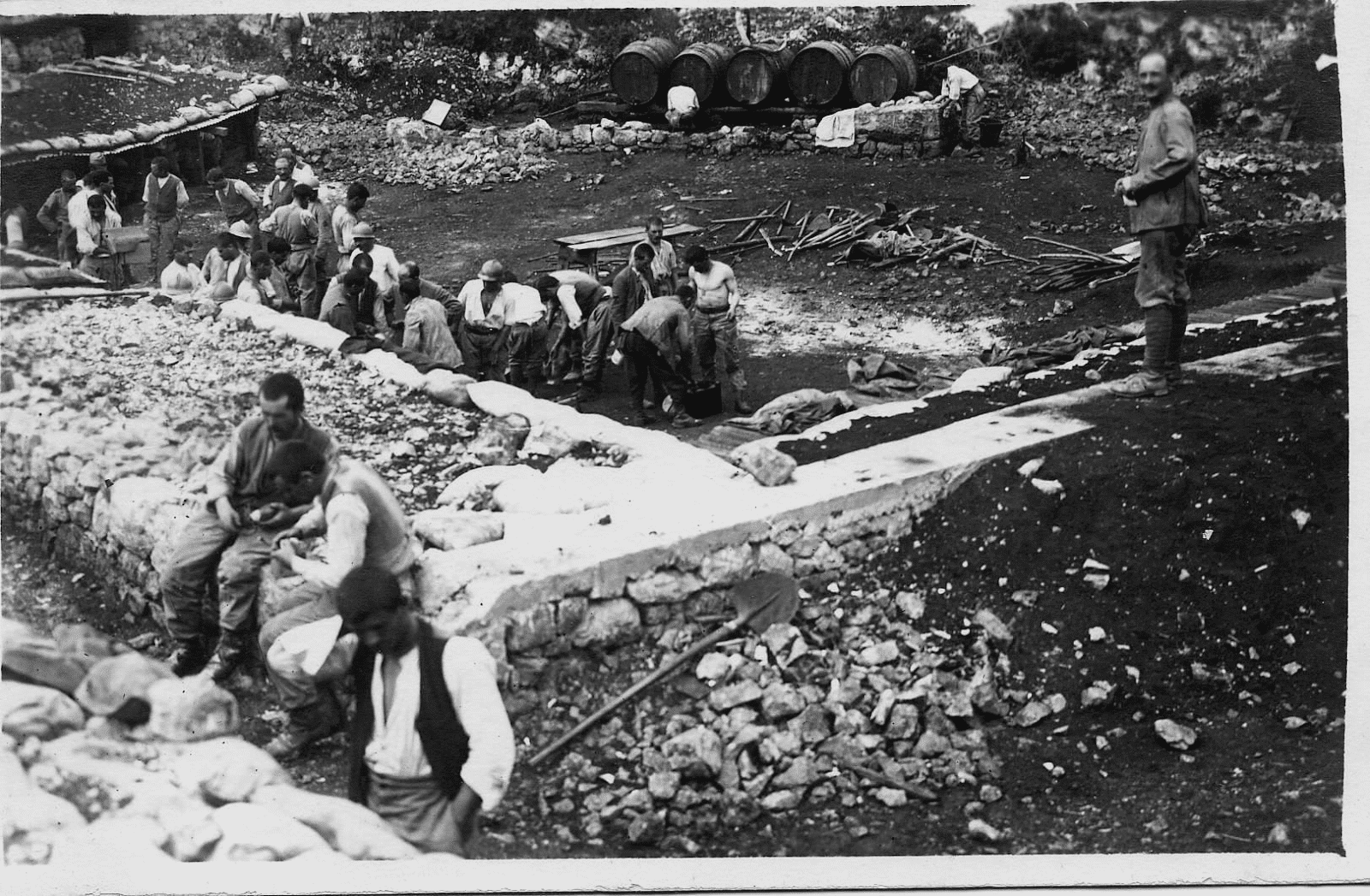

Today in the territory of the Municipality (now called Campolongo Tapogliano), the remains of World War I are still remarkable: concrete entrenchment systems made by Cadorna behind the front to contain a possible Austrian breakthrough. Their construction brought many workers from all over Italy to the site. There is also a plaque then placed by the Command of the XIII Army Corps to commemorate the civil and military deaths (34 people died and 34 were wounded) of an unfortunate explosion of ammunition that took place on the town's main street on August 4, 1916 during the preparations for the Battle of Gorizia.

I Soldati

When the “Class of 1895” (my father's group) was called for conscription over 90% of the eligible men complied, despite the general lack of interest by rural and lower class people for the declaration of war.

The army in 1915 was composed of 96 infantry regiments (rising to 236 over the course of the war), which were arranged not on the basis of regions or localities, but instead were recruited from at least two different regions and stationed in a third. Italian men met and mingled with others from all over the country, and had the chance to feel that they were part of something much larger than themselves. To take one example at random: the 111th infantry regiment, part of the Piacenza Brigade, included men from 27 different locations between 1915 and 1918: Milan, Como, Lecco, Bergamo, Brescia, Piacenza, Varese, Lodi, Genoa, Venice, Ferrara, Parma, Jesi, Livorno, Florence, Arezzo, Rome, Naples, Reggio Calabria, Messina, Catania, Catanzaro, Sulmona, Syracuse, as well as Soazza and Melvagia in Switzerland, and six men born in Africa. This represents a variety of men from the north, center, south and islands.

The process of military service could help educate ordinary soldiers about what Italy was and what values it represented. These encounters were a critical element in constructing an “Italianità” which was reliant primarily on the lived experience.

More important than geography and architecture, in men’s letters, diaries and memoirs it was an almost universal norm to comment on the geographical origins of every new acquaintance. New friends, travel companions, members of the platoon or company, as well as officers and NCOs, were all identified by regional origin. Men were keen to recount regional differences, often describing the exchange of local customs or foods (especially desserts) as well as shared activities, e.g. prayer and singing.

Of course alongside interest in fellow nationals there are many examples of regional prejudice, especially towards Southerners. These prejudices could also of course act to limit the development of a strong national identity, as could strong regional or local identities. If men identified themselves primarily with a locality, it was hard for Iitalianità to seem valid or important. And many men recorded their delight at meeting up with men from their own town or area, even if they were strangers: amid the dislocating, disorientating experience of war, men from home were a source of comfort which could not be easily substituted. Yet the opportunities provided by mingling with men of diverse geographic origins should not be underestimated, offering at least a likely basis for the construction of an Italian national community. Some examples of this new community and also regional prejudice and overcoming it:

- Amadeo Rossi of Cesena was in Venice undergoing training when the war began and his time in that city made a huge impression on him, overwhelming him with its beauty, culture and civilization, and giving him a much better sense of what ‘Italy’ meant. He wrote of “our beautiful Venice”. A sense of ownership gradually developed through his time in the city, where, crucially, he was not a tourist but a member of its defending force.

- “I am with two men from Bari and they are like a piece of bread [i.e. good, wholesome] every evening we say our prayers together” wrote another Cesena man.

- When the Neapolitan Armando Diaz was appointed as Chief of the General Staff in November 1917 some similar prejudices emerged. Official historian and staff officer Angelo Gatti observed the resentment of “the Piedmontese nobleman [General Mario Nicolis di] Robilant, who will certainly not be happy to work under the Neapolitan Diaz”.

- A Romagna man wrote, “I am well I’m alone but there are some [men] who are frightening and it is always those Neapolitans”.

This complex situation, and the daily encounters between men from different parts of the country, necessitated a new means of communication – a shared language, which could help constitute a shared identity. What happened, therefore, was the growth of standard Italian – or rather that variant known as “italiano popolare”. This variant offered new communicative possibilities between men of different regions and localities who could build a sense of collective identity – both within the context of their military units, and within the context of the nation. Italiano popolare was also strongly associated with the need to acquire at least some degree of literacy, a significant feature of the peasant experience of the war. Many learned to read and write for the first time in the trenches, while those who had acquired some level of literacy before the war found themselves actually putting their skills into practice, reading and writing regularly for the first time in their adult lives. Of course, correspondents at home were also working to develop functional literacy skills at the same time.

My father appeared to have encountered all these attributes of everyday life of the soldiers and a sense of “Italianità”. In regards to the geographical aspect, the house on Market Street in my home town, where he lived with his sister and brother-in-law for over 20 years, were exquisite murals painted on the walls showing scenes of Italy (not only Abruzzo but other regions). Significant among these was the painting of Trieste – perhaps an acknowledgement of his four years of service in the Italian Army pursuing “Italia Irredentia”.

In regards to friendships with fellow soldiers from other regions in Italy, he deftly called upon a soldier friend (probably from Rome) whose assistance he needed to get clearance from Italian authorities to get passports for himself and sister (and her future father-in-law). In 1921, new American immigration rules required many administrative details which he was able to overcome with the help of his friend from the regiment who worked in the Italian Foreign Ministry.

Finally, letters home put into practice the basic elementary education he had received in regards to writing and reading. He gained literacy from semi-literacy and maintained his ability to read and read Italian, as in such periodicals and the Italian American newspaper, Il Progresso, among others.

My Father's Battles at Isonzo Front

The Front Lines

The year 1916 opened with the Macerata Brigade behind the lines on New Year’s Day but on the very next day, they returned to the front at the Castelnuovo sector and to the front lines at trenches Trincea delle Celle and Trincee Rocciose. For recognition, each trench was given a name, which referred to the characteristics of the surrounding area (as in the case of the trench of the cells (Celle) or of the so-called "rocky trenches" - Rocciose), or to the conformation of the trench itself (small trench, trench triangular, etc). The Brigade is sent to relieve the Sassari Brigade. Infantrymen had dedicated themselves to the consolidation and improvement of the defensive lines. On the far right of the Frasche trench there was a walkway just 80 cm wide; it was not dug into the ground, but protected by bags of earth for forty meters until it reached six meters from the Austrian trench. It was called the Budello (See tottus in pari, emigrati e residenti: la voce delle due "Sardegne", 13 maggio 1916). This position was manned by thirty men and two officers. They had a series of lighting rockets that were to be launched to pinpoint, according to the number, the immediate intervention of medium and larger calibers of the Italian field artillery. A battalion was always ready to intervene to protect that 32-man garrison.

On the January 23 the Brigade returned to the rear again between Campolongo and Armellino; less than two days later elements return to the front less two battalions (awaiting typhoid vaccinations) to reinforce the Sassari Brigade, engaged in a strong action at that time at the Budello. On the January 26, the commanders and two battalions return to the rear, leaving two battalions at the front (in reinforcement).

|

| This diagram shows the location of the trenches occupied by the Macerata Brigade during 1916 and also shows the road back to the Command Post for the Brigade at Castel Nuovo. |

Thus, the first two months of 1916 passed in a continuous alternation between the Macerata Brigade and the Sassari Brigade in presiding over the Trincee delle Frasche and dei Razzi and in the rest periods in Campolongo al Torre and in Armellino (Isola Vicentina).

The Brigade remains at the rear until February 10 at the Campolongo-Armellino area. On February 11, the brigade returns to the Castelnuovo sector as part of its rotation to the front lines occupying Trincee delle Celle and Rocciose. Elements are also at Trincea delle Frasche) also in the Castelnuovo sector. As part of these short rotations the Brigade returns to the rear on March 1 until March 10. No firefights are reported during the rotations. However, this front (war zone) was open to almost continuous skirmishes and small platoon size actions in between the large scale offensive actions planned by General Cadorna and called the Battles of the Isonzo.

|

| Ruins at Trincea delle Frasche (“Leafy Branches”) |

The Battles of the Isonzo were a series of 12 battles between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian armies along the Isonzo River on the eastern sector of the Italian Front between June 1915 and November 1917. As we have seen the Brigade participated in Second and Fourth Battles in 1915. See Part 1.

The Fifth Battle of the Isonzo

Italy launched the Fifth Battle of the Isonzo on March 9, 1916. This was an offensive launched not after detailed strategic planning, but rather as a distraction to shift the Central Powers away from the Eastern Front and from Verdun, where the greatest bloodshed of the war was occurring. The attack was a result of the allied Chantilly Conference of December 1915. Luigi Cadorna, the Italian commander-in-chief, organized this new offensive following the winter lull in fighting which had allowed the Italian High Command to regroup and organize 8 new divisions for the front.

The attacks ordered by Cadorna for the 2nd and 3rd Italian Armies as "demonstrations" (comprised of local assaults) against the enemy, proved to be less bloody than the four previous battles. The battles were fought on the Karst plateau, with the stated objective of taking Gorizia and the Tolmin bridgehead, an Austrian water crossing at Tolmino located north of Gorizia on the opposite side of the Bainsizza Plateau. The Italians were able to conquer Mount Sabotino (overlooking Gorizia) from the Austro-Hungarians, but that was the only real gain made. The Karst sector was contested by the two opposing (static) armies in trenches opposite Gorizia and Monte S. Michele. It was also important that certain local operations were conducted in the winter period, serving to maintain aggressiveness in the troops, otherwise engaged in the endless work of maintaining the trenches, which were continually destroyed by enemy artillery. Every month 300 million bags of earth and ten million kg of lime and cement were used for the restoration and conservation of defensive works, as well as three and a half million meters of barbed wire.

An example of the fighting at the Castelnuovo sector indicates that the Italian infantry was to advance beyond the Budello. However, the Italian artillery had not managed to destroy the enemy barbed wire and even with the use of gelatin tubes (by the infantry) because of the enormous depth placement of the barbed wire. It was decided to put jelly tubes under the barbed wire of the Tortuosa, the “Winding Trench” close to the Budello. Immediately after the destruction of the defensive works a small group of Italian Arditi (Special Forces) rushed into the enemy trench, managing to eliminate the lookout. Then battalions of the regiments intervened. The explosion of an Italian grenade in the trench caused serious losses and the Austrians, who had come forward in large numbers, got busy, engaging in a wild fight with the survivors and with a group of infantrymen, who intervened to help the original special forces. The losses were serious.

|

| Fortifications at Castelnuovo del Carso |

The 121st Infantry Regiment (Macerata Brigade) of my father took part in these battles. This was likely the first major combat action of his career since he had just arrived at the war zone on December 2, 1915 and major fighting on the front had generally ceased shortly thereafter for winter. The Brigade rotated at the familiar Castelnuovo del Carso sector and was at Trincea delle Frasche, Trincee dei Sacchi and degli Scogli - Quota (Hill) 112 and Trincee dei Razzi and Rocciose.

After a week of fighting that cost the lives of 4,000 men between both sides, the clashes ceased (March 17) because of terrible weather conditions that worsened the trench conditions and because of the Austro-Hungarian Strafexpedition offensive in the Trentino. Cadorna then called upon his Russian allies to keep the Austria-Hungarian units at bay on the Eastern front giving Cadorna the chance to redeploy his forces at Trentino all the while abandoning the Fifth Battle of the Isonzo.

On March 19, the Macerata Brigade was relieved from the front and returned behind the front lines for rest, training and other work details. They were encamped at Campolongo (al Torre), Armellino and Aiello del Frulio, until May 8. As an indication of the less deadly nature of this Battle the total Italian casualties were less than 2,000, whereas, the first four battles AVERAGED casualties of over 42,000.

But my father had survived his first battle.

|

| Troops at Trincee dei Razzi (Rockets) |

Along certain parts of the front, especially around Gorizia, skirmishes continued between enemy platoons until March 30 and beyond, in a protracted struggle that produced no clear victor. One of these areas was another height above Gorizia – Monte San Michele. Even Castelnuovo remained dangerous. On 27 April, an enemy grenade, exploding in a barrack on the Castelnuovo estate, had caused another serious loss in the Italian ranks. The villa of Castelnuovo was hosting the command of the 25th division (of which the Brigata Macerata was part) and this was a real war town fortification - several artillery posts had been set up in preparation for future offensives, the opposing lines of the two armies were located just beyond the villa, which had become a place for marshaling, sheltering and massing troops, as well as having a medical group for initially treating those wounded in battle.

However, prior to the continuation of the larger Battles of the Isonzo by the Italians, the Austro-Hungarians had planned a major offensive in Trentino. The Macerata Brigade would not participate in this action but would later be involved in several Battles at the Isonzo that followed this Austrian Strafexpedition.

Again my father would soon see more fighting with his regiment. See Part 3.