This is a personal history of my father's time spent in World War 1. My father was an Italian who served in the Brigata Macerata from 1915 until 1919. He was in the 121st Infantry Regiment (Reggimento di Fanteria). He fought in the Isonzo (1915-1916), the White War (1916-1918), the Piave (1918) and in the ultimate Battle of Vittorio Veneto (1918) against the army of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Americans (and indeed the British, French, and others) probably do not know this war in Italy so much. Well, here is a little history lesson (in several parts) to remedy that ignorance. The story begins in Teramo Province in Abruzzo. The story starts out slowly with typical rural Italian life

Clouds of War

The Old Life

On June 28, 1914, the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Crown Prince, Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo was to affect the lives of millions of young men throughout the world. One of those young men was my father. He was a 19 year old son of a contadino (farmer who either owned some land or worked for others not owning the land, like a sharecropper). His mother had died in approximately 1900, leaving my grandfather to fend for three young children – my uncle age 7, my father age 5, and my aunt, age 2.

By 1909 my grandfather had remarried and had two additional sons born in 1909 and in 1913. Later two other children would be born – a daughter in 1916 and a final son in 1919 - to complete the family.

My father would have likely been working with his father helping him farm and take care of this family. The story passed down is that my grandfather was a type of sharecropper, a system known as the mezzadria. Large landowners (padroni) would divide their land into sections and allow other families to live on it and grow crops. Half (or some other percentage) of the produce (or the revenue from the sales of such) would go to the landowner. My family by the accounts of my aunt did well enough. A typical farmer in Abruzzo would have produced all the food needed to feed his family. Four or five people could survive on the produce of one ettaro (hectare - about two and a half acres) of land. The family took care of everything, like a small family-run farm. Generally, everyone knew how to do everything, but everyone had their specific tasks. Their plot would have grown a large variety of vegetables the same as are seen in farmers’ markets today, including carrots, potatoes, beets, garlic, onions, radishes, turnips, artichokes, tomatoes, eggplant, asparagus, fennel, chard, spinach, broccoli, cabbages, cauliflower, peppers, beans, lentils, chickpeas, zucchini and other types of squash, and peppers. Years later in America my father would grow many of the same vegetables in his backyard plot. Whereas our “American” neighbors would have a yard of flowers and grass, our backyard was filled with vegetables (every square foot). In addition to the vegetables, wheat and corn was probably grown. Then they would have had fruit trees: apples, pears, apricots, peaches, figs. Every family had its own livestock - chickens, pigs, rabbits, sheep and cows (for both milk and meat). Extra eggs, vegetables and fruit would have been sold at the markets in old Atri or in new and growing Pineto.

Life Changing Events

- Austria-Hungary had sought German (its ally) support for a war against Serbia in case of Russian “militarism”. Russia had close relations - almost as a protector - but no formal treaty with Serbia (both countries tied together by their large Slavic populations. Germany gave assurances of support. (July 5) This was weeks before the Austrian declaration of war;

- Germany declared war against Russia (August 1);

- Italy, a member of the Triple Alliance (with Austria and Germany) declares neutrality (August 3), claimed that its pact only applies to defensive actions. Italy’s actions seemed (to its citizens) that war would be avoided by Italy;

- France mobilized (August 1) in response to the declaration of war on Russia. France had a military alliance with Russia:

- Germany declared war on France. (August 3);

- Germany invaded France through neutral Belgium. (August 4) In response the United Kingdom declared war on Germany (August 3) as a violation of the Treaty of London (1839) – guaranteeing Belgian neutrality;

- Austria declared war on Russia. (August 6);

- Serbia declared war on Germany. (August 6);

- France declared war on Austria. (August 11);

- the United Kingdom declared war on Austria. (August 12)

|

| Interventionist demonstration at the Spanish Steps in Rome (May 1915) |

Intervention demonstrations in Italy keep increasing in number, size and location - impressive interventionist demonstrations were everywhere. In Rome Giolitti deputies are insulted and beaten up; in other places, as in Milan, there are physical conflicts with the neutralists. On May 13, knowing that the consensus of the elected parties is lacking Salandra presents his office’s resignation of the government to the King, who reserves the right to decide, and which is ultimately rejected on May 16. These acts appeared to put the government over the top for intervention. Five days later, the Italian Senate unanimously approved the bill granting full war powers to the Government. The news causes the closure of the border between Italy and Austria-Hungary (including rail and telegraph). In Italian speaking Trieste (then in Austria), military law was proclaimed. This vote is followed by the Parliament, under pressure from the interventionist demonstrations, for approval, with 407 votes in favor, 74 against and 1 abstention, for the bill conferring to the Government the extraordinary war powers.

|

| The Customs House at Trivignano Udine on the border with Austria, near the Torre River. |

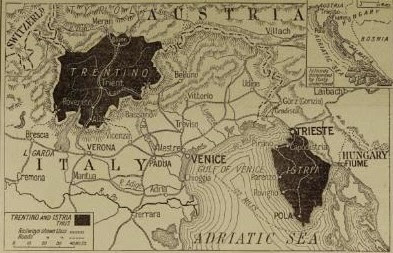

On May 22, Italy instituted a general military mobilization to increase the size of the military - R.D. May 22, 1915 Circular of the G.M., under which the King has decreed the general mobilization of the army and navy and the requisition of equipment. The mobilization was set for the next day. With this communiqué King Vittorio Emanuele III prepares the country for the conflict. In the provinces of Sondrio, Brescia, Verona, Vicenza, Belluno, Udine, Venice, Treviso, Padua, Mantua, Ferrara and in those of the Adriatic, a state of war is proclaimed. On May 23 Italy declares war on Austria-Hungary, although not on the Germany (which will occur until 15 months later, August 28, 1916).

|

| La Stampa, Turin: Headline of May 23, 1915 announcing the General Mobilization (War Declaration Not Yet Announced Until Later that Same Day) |

|

| Part of my father's Italian Military Record, the Ruolo Matricolare which records all the developments in a military career, from promotions to changes in status. |

New Life

“The unit is composed almost entirely of the class of 1896 whose hasty instruction (little more than three months) has not been sufficient to ensure an adequate preparation for the campaign, either with regard to technical training or with respect to physical endurance.”

“We received our first lesson in ‘open order’ and ‘tactics.’ Our lieutenant explained in minute detail the essential rules: be silent, obey signals, always look at the officer in charge, adapt movements to the ground, use shelter in order to offer the smallest possible target, never drop vigilance and observation in order to guard against any surprise.”

This description suggests that trainers acknowledged the need for greater tactical sophistication than close-order drill alone would permit but emphasizing the need to follow the officer closely in all things left infantrymen lost and unable to proceed without leadership – if officers fell during combat, their men had no experience in taking the initiative themselves.

The acute shortage of experienced officers and NCOs who could conduct effective training was another cause of these problems. Alpini Lieutenant Garrone recorded that he was “daunted” by the scale of his task in training his men, and complained that he had been given insufficient guidance and support. Since officer training was itself weak on practical matters, tactical instruction and personnel-management, junior officers' task was an unenviable one.

Along with time and experienced instructors, the Italian army was critically short of equipment. Weapons handling and target practice, among the most fundamental elements of infantry training, were deeply flawed. Any form of firing practice was difficult given the acute shortages of equipment. In August 1914 the Italian army had at its disposal 750,000 rifles of the 1891 model, supposed to be the standard, and no hand grenades at all. Training was therefore sometimes carried out with just one or two rifles per company, each man taking turns with the weapon. Gino Frontali described the situation in late 1914:

“Target practice suffered from a most serious defect. It was done in a great hurry… we fired two rounds (twelve shots each) every week. This exercise was sufficient to familiarize us with the use of the rifle, but not to establish any precision of aim. One saw progress only rarely. Those who [already] shot well, who had a passion for hunting, improved a little after the first lessons. The others, the majority, hit the target only rarely, and no-one seemed concerned about it.”

|

| A panorama of a portion of the training camp (campo di addestramento) at Porretta (Modena) |

The Italian Front Overview

|

| The Italian Army advances in May 1915 into areas abandoned by the Austrians for defensive positions in the higher mountains (blue) and the Austrian mountain defenses (red) |

Young Soldier - 1915

Arrival at the Front

On December 2, 1915, my father arrived in territory “declared in a state of war”, i.e. the war zone, to the 121st Infantry Regiment (RF). The unit was located at the front line at the Castelnuovo del Carso Sector.

One cannot imagine arriving at an area where people are waiting to kill you in battle. The young farm-boy who until some months ago had probably not ventured very far from his home in Abruzzo now ventured into Venezia and Fruili. The following is an excerpt from a diary by someone probably much like my father who arrived in this same time frame in November 1915. Domenico Bodon, a private with the Chieti Brigade (124th Infantry Regiment), who arrived behind the front lines at Ruda/Villa Vicentina on November 7, 1915 wrote:

We are very close to the front, all around houses are destroyed.

In a town where the train is forced to stop, there is a huge camp and in the middle, the Italian flag. 11 am. The village is called Villa Vicentina, the last station as the train can no longer continue, because the enemy lays further on; I'm still on the train and without food since last night. We disembarked and the appeal is made to stay close to it. Nice weather. The cannon thunders continuously. It starts at 11 and a quarter. At one and a half we are facing the enemy on the spot where the shrapnel landed this morning. You can see the holes made without misfortune. Still wanting to eat and I find myself in a field full of mud. After 2 hours of waiting we were ordered to wait.

Oh God! In that mud, where, now traversed by other soldiers, you sank to the whole shoe. Patience! We planted the tent and meanwhile those of us 5, destined for this work, were free, went in search of straw, something to put down our poor bones. In the end everyone got sweaty and then he went to get the bedding getting 4 kilos for each one.

5 o'clock in the evening. We are at the end. Meanwhile, we talk with several companions who tell us the name of the locality is Ruda. The night comes and at 7 pm the ration came: a little pasta and a nice piece of meat, almost raw; but hunger is so great that we had to swallow it to pieces. The thirst began; and where in the night to find the water? A companion showed us the point and then we started splashing in the puddles. We reached the fountain and drank to fullness. And then a mess tin brought it to me under the curtain.

So here we are at night high, prepare the bed, we will say, without lighting matches, all groping. In the meantime, one was preparing, the other waiting, until the last one arrived to close. I was the last one.

In that time I was waiting, a show of the most gruesome presents itself to me. On the Isonzo front, there are always great reflections, but many, that run with their trajectory of long pieces, so that our, under that strong clear, could see the enemy pieces; and then the cannon that was ready fired with a tumult that in the middle of the night was disgusting. Know among other things that we are stationed near a cemetery. At the same time you can also see the shrapnel split in the air and then maybe do damage that I cannot explain now. In short, I was so impressed that I immediately went to bed with the idea that perhaps among those 4 sheets to stay safe.

It is unlikely that my father was thrown immediately into the front. On 14 December, the 121st RF is relieved at the front and goes back to the rear at Campolongo and Armelino, near Ruda. The Regiment remains there until January 2, 1916. So there was no combat in 1915 for my father.

While the Regiment is in the rear, one of the primary roles is to continue to train itself and its new members of the group such as my father. These young men are not yet soldati (soldiers) and know very little of what they are facing. The 121st Regiment was part of the Macerata Brigade. The Brigade was established on March 1, 1915. The Brigade command and its brother 122nd Regiment were taken from the 12th Infantry Regiment; the 121st Regiment from the 93rd Regiment.

It is not known to which Battalion my father was assigned, either infantryman or special weapons or in a pioneer unit as a “genio” / “zappatori” or engineer/sapper. The Army’s basic unit was the “Regiment”. Each Regiment at full strength consisted of three “Battalions” (of 1000 men each, further divided into four “Companies” of 250 men. Each Battalion had three rifle companies and one special weapons company generally with a machine gun squadron, a mortar squadron and a pioneer platoon, tasked with construction duties.

“Macellata” - Brief History of the Macerata Brigade in 1915

The Macerata Brigade by the time my father reported had become known as the “Macellata” Brigade which means butchered/slaughtered – a play on the official name of the Brigade. This nickname is typical "gallows" humor of soldiers and the reason for this nickname becomes evident when the history of the Regiment in battle is uncovered.

The brigade fought in both the Second (August) and the Fourth (November) Battles of the Ionzo. These battles included brutal trench warfare at Redipuglia and the trenches Rocciosa, dei Morte and Razzi. These actions were recognized by the Italian high command and resulted in the award to the Brigade of the Medaglia d'argento al valor militare (which became part of the Brigade’s emblem). The Brigade returns to the rear on December 14 to Campolongo and Armelino for the remainder of the month. Total losses (deaths) for 1915 were 92 officers and 2,796 men constituting a loss of nearly half the Brigade and giving the Brigade the unfortunate “Macellata” nickname.