Schuylkill County was once a territory within the homelands of the Lenni Lenape and Susquehannock native tribes. neither of these tribes had permanent settlements in this territory but traversed the area as a place to mostly hunt and trap. The territory was also crossed by documented Indian trails were the native peoples in the northeastern part of what was to become the United States traveled between their homes and other tribes (for trade or occasional wars) or for access to the bountiful game for food and other necessities (furs for clothing and blankets). The Schuylkill County of today have some evidence of these links to its native past - Indian fields, place names, even evidence if the old Indian trails, if you look closely enough. But this article is about a truly unusual artifact that attests a link to Schuylkill County that is tangible and conclusive.

|

| Spirit Mesingw as found in Schuylkill County. The dimensional reference is a 12-inch ruler. |

The discovery of the Mesingw petroglyph

On May 10, 1968, a fascinating discovery was made on a hillside of West West Mountain along the west branch of the Gordon Nagle Trail (State Route 901) about two miles from Llewellyn in Branch Township, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. Francis P. Burke of Mar Lin was traveling near the west branch of the Schuylkill River looking for Native American sites. He saw a dark area in the hill and, thinking it indicated a rock shelf, followed a path into the mountain to investigate. The path led to a small clearing, but after following a small stream that ran through the area he realized he had gone too far but hadn’t yet seen anything.

Going back from where he came, he now observed a niche and then an area opened up. He saw a little part of a sandstone boulder. The rest was covered over with brush and a laurel bush. Working to remove the debris and he first saw a mouth, then a nose, then two eyes. Burke said, “I got the thrill of my life.” He had happened upon a petroglyph, a rock (sandstone) carving, dating back to the 17th century and thought to be a representation of the Lenni Lenape (Delaware Indian) spirit Mesingw and now located in The State Museum of Pennsylvania in Harrisburg. [See Richardson, Leslie, Locally discovered petroglyph replica on display at county historical society, The Pottsville Republican, October 19, 2009]

Mesingw is an important Lenni Lenape spirit being who rode through the forest on the back of a large deer; Mesingw is believed to have made sure that all the animals were healthy and fed. Lenape hunts were believed likely to be more successful if Mesingw was remembered and commemorated.

Schuylkill County was once within the homelands of the Lenni Lenape (known as the Delaware by the settlers) people. The Lenape were part of the Unami- and Munsee-speaking (Algonquian dialects) peoples of the Delaware, Lehigh, Schuylkill, and New Jersey and lower Hudson (New York/New England) River valleys. At the time of the coming of the Europeans, the entire area occupied by the Lenape was known as Lenapehoking. Schuylkill County was located (mostly) in Unami territory (the Schuylkill and Delaware - below the Lehigh - river areas).

|

| Lenapehoking |

Surrounding Lenapehoking, were other unrelated native people groups. To the west, beyond the Schuylkill River, were the Susquehannock who occupied most of the Susquehanna valley down to the Cheasapeake Bay and west into the Allegheny Mountains. The Susquehannock were Iroquois speakers, a distinctly different native language group. Part of the homelands of the Susquehannock also encompassed the western parts of Schuylkill County.

However, neither the Lenape nor Susquehannock had permanent or semi-permanent communities within the future borders of Schuylkill County. Both indigenous groups lived in semi-permanent villages exclusively all near larger rivers – the Delaware, the lower Lehigh and lower Schuylkill – and in the case of the Susquehannock – the Susquehanna, where the inhabitants lived for ten to twenty years and then moved on to new areas as the land became exhausted from farming. Schuylkill county, was mostly a place where the groups of each tribe would travel to several times each year to hunt, fish and trap.

Mesingw and the Indian path to the hunting grounds

Moreover, Schuylkill County was the locus of four “Indian trails,” the interstate highways of early native and then European North America. These four paths began in the present-day Reading area, where they connected to other paths to the east and south. Reading lies on the Schuylkill River upstream (about 60 miles from from Philadelphia). It became a center of the Indian population as settlers moved into the Bucks, Philadelphia and Chester County areas that had been purchased by William Penn in the 1680s. These four paths themselves led to other trails into the deeper interior of Pennsylvania and also to New York (home of the Five Nations Iroquois) or to the west in Pennsylvania, further and deeper into Indian territory towards the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley west of Pittsburgh. These four paths are:

• Tulpehocken Path between Wolmelsdorf (west of Reading) and Shamokin (present day Sunbury),

• Schuylkill Path between Reading and Shamokin,

• Catawissa Path (east) between Reading and Catawissa, and

• Nanticoke Path (north) between Reading and Nanticoke.

Of interest here is the Schuylkill Path because that appears to be where Burke discovered the Mesingw petroglyph. This path was also a forerunner to the Kings‘s Highway (1770) and of the Centre Turnpike (1809).

In the earlier Indian Era it appears that this path was a route that intersected with the Maxatawney Path from from Lechauwekink (Easton) at the Forks of the Lehigh River and thus provided a route from Easton to Sunbury that may have been faster that from Easton to Sunbury using portions of the Maxatawny Path, Lehigh Path, Nescopeck Path and Great Warriors Path.

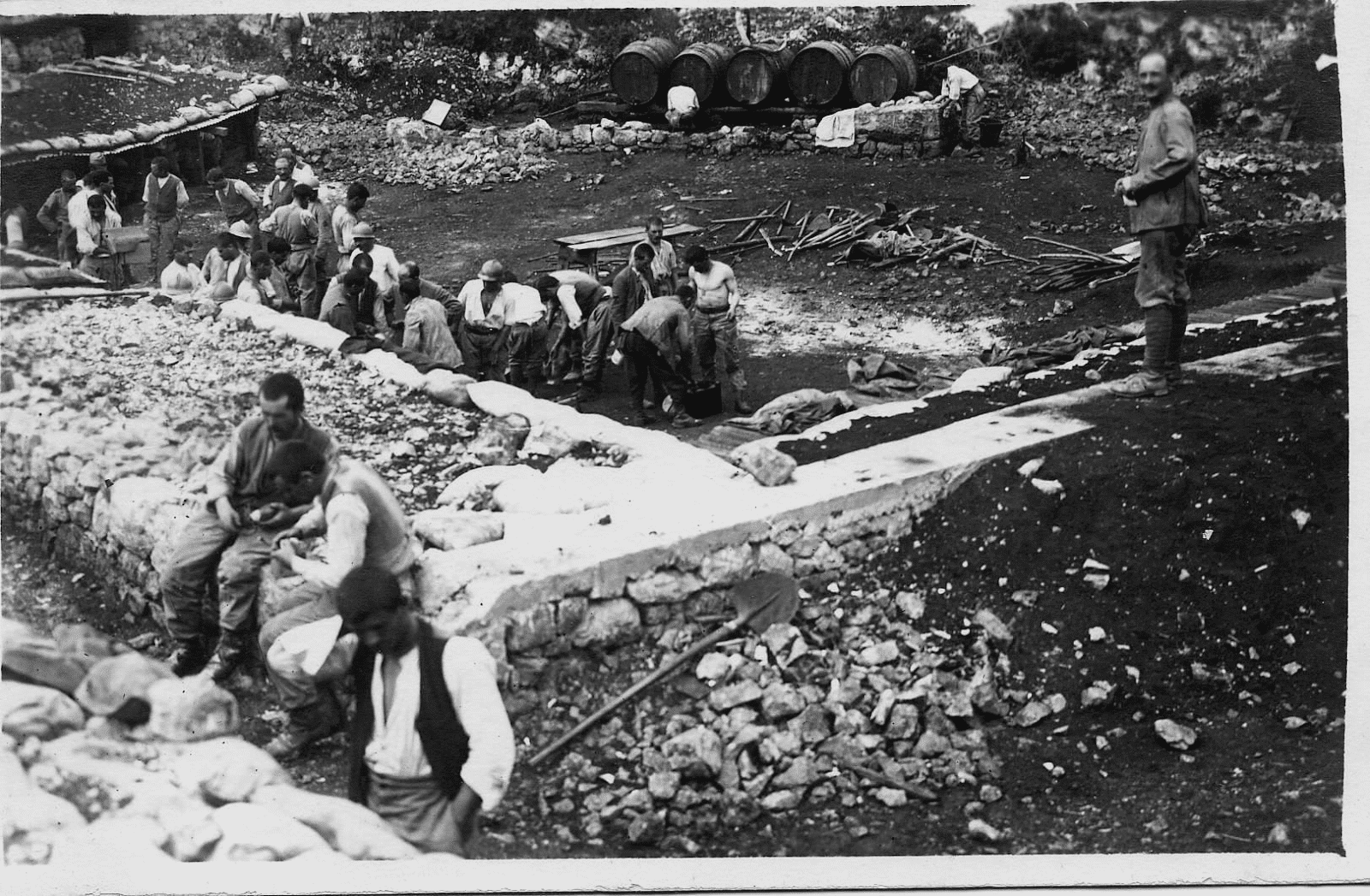

|

| The petroglyph when it was discovered in its natural state somewhere near the Schuylkill Path |

There was also an Indian settlement at Maxatawny (Kutztown and vicinity) to Maiden Creek and Reading. The area now comprised in Maxatawny Township was much desired by the Lenape Indians, who remained here for some time after white settlers surrounded them from the east and south, maintaining relations with the newcomers, until about 1736, when these lands were purchased by Penn’s proprietors. There is a lack of explicit evidence for this traditional Indian path. But the known presence of so many natives in Maxatawny presupposes connections with the Forks of the Delaware and the Indian paths radiating from it, as also with Reading, where the Allegheny Path from Philadelphia to Harrisburg and Pittsburgh crossed the Schuylkill River. There is also reason to believe that hunting, trapping and fishing in the Upper Schuylkill was an attraction that drew Indians from Easton, Philadelphia and the Susquehanna areas into the headwaters of the Schuylkill River. As noted this area was devoid of permanent Indian settlements so likely a good place for Indians from all regions to visit for these reasons.

The presence of Indian fields in the Upper Schuylkill area also supports this theory as does the use of “hunter’s hints” in place names in this area. According to Mahr [Mahr, August C., PRACTICAL REASONS FOR ALGONKIAN INDIAN STREAM AND PLACE NAMES, THE OHIO JOURNAL OF SCIENCE 59(6): 365, November, 1959, p. 368], whether on the go or at home, the Lenape Indians, men, women, and children, mainly subsisted on meat. Plentiful hunting, therefore, was not a luxury but a necessity. Hence, it was an advantage to the tribe to be familiar with names for localities where the hunters were most likely to find enough game animals to supply the common need. On modern maps, for example, there occurs place names such as Tamaqua, Maxatawny, Macungie. Heckewelder [John Heckewelder was a Moravian missionary to Pennsylvania from 1754. See Heckewelder, J. 1834. [On Indian names.] Trans. Amer. Philos. Soc, n.s. 4: 351-396. 1881. History, manners, and customs of the Indian nations who once inhabited Pennsylvania and the neighboring states. 450 pp. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia] listed the true Delaware name form for present Tamaqua, referring to the Little Schuylkill River (Heckewelder, 1834: 361). He wrote Tamaquon and stated that its correct Delaware version was Tamaquehanne "or (short) Tamakhanne, the Indian name, as it stands on record, for Little Schuylkill." His interpretation is "beaver stream." Similarly Heckewelder established Maxatawny as Machksithanne and interpreted it as "bears' path creek or the stream on which the bears have a path" (Heckewelder, 1834: 360), and another such hint at good bear-hunting was Macungie. Heckewelder gave its Delaware form as Machkunshi (spelling modified), which he rendered as "the harboring or feeding place of bears" (Heckewelder, 1834: 357).

Finally, a great many “hunters'-hints” names, however, made no such special mention of the game which they promised. Their hints were broader. It was well known, for instance, among the Delaware that there was good hunting of all sorts of game near any natural outcropping of salt, be it a salt lick or a saline spring which equally attracted the animals. That is why in the whole Lenapehoking the Lenape hunters formed numerous names for big and small water courses with their term m’honi, “a salt lick,” usually adding to it their locative final -’nk: m’honink, “where there is a salt lick.” Because of salt licks in their head waters, several such streams were called m’honink siipunk, or m’honink/ hdnna, “river where there is a salt lick.” And so it is along this Indian Path. In Schuylkill County, there is the Mahanoy Creek and (Mahanoy Township and City).

The path starts near Saconk, an Indian village at the confluence of the Schuylkill River and the Maiden (Ontaulanee) Creek (Berkley), which was the terminus of the Maxatawny Path. The path runs along side the Schuylkill River through Leesport, Hamburg to Port Clinton. The Path crossed the Little Schuylkill River south of Molino and then to Deer Lake and Schuylkill Haven. Then the path followed the West Branch of the Schuylkill River to Yorkville and Minersville and then turning west [this describes Route 61 and then Route 901] towards Beury’s Lake past Deep Creek headwaters. [The bold text describes the area where Mesingw was discovered - Llewellen.] The path continues to the north to Taylorsville to cross the Mahanoy Creek and then the Shamokin Creek in Mt. Carmel. The path continued west re-crossing the Shamokin Creek at Paxinos and then to Stonington, Oaklyn and Sunbury (Shamokin). [This latter part describes Route 54 and then Route 61, again.] (See Wallace, Paul A., HISTORIC INDIAN PATHS OF PENNSYLVANIA, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1952, drawing between pp. 438 and 439)

|

| The Schuylkill Path – Saconk to Shamokin, following the Schuylkill River and where Mesingw was carved |

Mesingw (probably pronounced MUH-seeng-wah) means "living solid face" or "masked being" and he was the protector of all animals of the forest, but is most strongly associated with deer. Some Lenape people describe him as taking humanoid form and riding through the woods on the back of a deer, helping respectful hunters and punishing those who despoil the forest. His purpose was to reconcile the native's need for meat with the resentments of the animals who were the game.

The Lenape nation today considers Mesingw important enough to place a likeness on their official seal. The Mesingw face is in the center of the seal as the Keeper of the Game Animals on which the Lenape depended for food. The face was carved on the center post of the Big House Church ("Xingwekaown”), a wooden structure which held the tribe’s historic religious ceremony in Oklahoma (where the tribe was forced to live over the 19th century). To the right of the mask is the fire drill traditionally used to start sacred fires. Mesingw was so important that the Lenape would have a large gathering to celebrate its spirit. During this celebration, the mask painted 1/2 red and 1/2 black along with a fur skin was worn by a tribe-member to invoke the Mesingw's spirit. In that attire, he would then go through the forest.

|

| The seal of the Lenape (Delaware) tribe adopted in 2012. Mesingw was however also on the previous versions. |

This Mesingw petroglyph really exemplifies a connection between native Americans and Schuylkill County. It weaves Lenape traditions – religion, way of life (hunting, trapping and fishing), place-naming conventions, travel - with an artifact created in the county centuries ago.